Tom Bowen-History

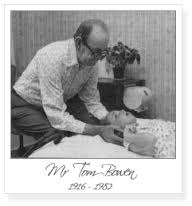

Thomas Ambrose Bowen 1916 – 1982

I expect to pass through this world but onceAny good thing therefore that I can do,

Or any kindness I can show to any fellow creature, let me do it now

Let me not defer or neglect it,

For I shall not pass this way again. – John O’London

The story of Tom Bowen is a remarkable one, even more so for knowing that in spite of being one of the busiest and most effective therapists of his generation, he had no formal training or qualifications in any therapeutic background.

His parents were originally from Wolverhampton and emigrated to Australia in the early 1900s settling in Brunswick, Victoria. A working class family, Tom left school at the age of 14, taking various labouring jobs, including milk carter and general hand at a woollen mill, before going into the building trade where he took up his father’s trade of carpenter, working as a general hand at Geelong Cement works.

He was married in the early days of World War II to Jessie and they lived with Tom’s parents in Geelong, Victoria. A keen Salvationist, Tom Bowen ran a Salvation Army Boys’ Club which was hugely popular and where he would coach youngsters in various sports especially swimming which was a favourite.

It was while he was working at the cement works that he started to treat people after work, coming home to wash and eat before commencing clinics that would often go on well into the night. With encouragement from friends Rene and Stan Horwood in whose house he operated his clinic, he eventually started to work full time out of a rented house in Geelong.

Having no therapeutic background Bowen was under no restrictions about how he should run his clinic and as such, appointments were vague to the point of non-existence. Patients phoning for a time would be told to come either morning or afternoon, when they would arrive, take a number from a board and wait. As the clinic times were only two hours long, and Bowen worked at a rate of something like 14 patients per hour, the wait would rarely be a long one.

Talk was minimal in Bowen’s clinic, with patients being told not to see any other therapist and that “If I don’t get you in two (sessions) go away and save your money”. Both points were good advice as Bowen was able to ‘see’ whether clients had indeed been treated by another therapist. In addition, the majority of treatments were first or second visits, Bowen not believing in extended therapy. Another reason for the minimising of chat, was that Tom Bowen was profoundly deaf and wore two hearing aids, often using a method of clicking his fingers to signify to his assistants when he had finished what he was doing. In addition to his deafness, Bowen had lost a leg possibly through diabetes (although this was never diagnosed) and walked around his clinic either using a prosthesis or not depending on his mood. He lost a second leg just prior to his death.

Romantic stories about how Bowen discovered his way of working have been spread around, including learning it in a Japanese prisoner of war camp, and spending time with Aboriginal elders where he was taught by them. Nice notions but sadly all untrue. Many of these stories and untruths from people in Australia have resulted in much hurt to the Bowen family who, until recently, have not had the opportunity to tell the full and true story.

According to evidence that he gave to the Osteopathy, Chiropractic and Naturopathic Committee Enquiry in 1973, he said that the only study he had undertaken was from books that he found useful and that all he had learned was self taught. All this alone gives an amazing overview of Tom Bowen but, I believe, misses the essence of how he was working and in many ways creates a very confined view of how the technique has developed.

His work with another therapist, Ernie Saunders, has been mentioned as being a strong influence on Tom Bowen and it is surely his exposure to consistent therapeutic approaches which gave Tom his ‘seeing’ ability. It was often said of Bowen that he could take one look at an individual and ‘see’ what was wrong and where the problem stemmed from. In addition he only needed to do a few simple moves, allowing the body to rest for certain periods, before ‘seeing’ that the body had started to change. Once he recognised this, his work was done and the patient discharged, maybe to be brought back next week or maybe for good.

It was common for the patient to walk out in the same pain as when they had walked in, a situation that many therapists would find uncomfortable and yet an excellent opportunity to see precisely what Bowen’s unique approach was. Tom Bowen’s work was not a systemised series of moves or techniques, but more a piece of music that would change according the mood of the orchestra and the temperament of the conductor.

What Bowen could ‘see’ was not something that could be verbalised or classified in the strictest sense of diagnosis. He just knew where there was an imbalance and had the ability to know when that imbalance was changing. If you’re pushing a car towards the cliff and it starts rolling, you don’t need to stick around to know that it’s going to go all the way. Similarly if the car is pointing downhill in the first place, then it’s not going to take much of a shove to get it going. Once Bowen had got the process moving, that was enough for him and he then knew that, through the week, the body would take over and do the rest. He was rarely wrong.

The physical action of what he did was secondary to knowing what to do, hence the refusal in 1982 by the Osteopathic Council to admit him as a member. Quite simply he wasn’t an osteopath in the accepted sense of the word; he wasn’t diagnosing structural abnormalities and using recognised techniques to address specific problems. His disappointment with his rejection was great, especially as it would have meant that his patients could have claimed their fees back from medical insurance and eased any financial pressure. Bowen was a selfless man in many respects.

He ran a fortnightly clinic for years, treated disabled people free of charge and he would regularly pay house calls to people who were unable to attend his clinic, even in the middle of the night. On Sundays he would visit Geelong Prison to treat prisoners and was many times called upon by the Geelong Police to assist them, even being awarded a medal from the Victorian Police Board. Over the years in practice, Tom Bowen had many people who watched him work and who learned from him, but six men are considered to be the main ones with whom Bowen shared much of his understanding and who were regarded as ‘Tom’s boys’.

One of the men, Oswald Rentsch, claimed that Tom invited him to learn after a handshake at a conference, such was Bowen’s ability to recognise the power of an individual’s touch. All these men were physical therapists in some regard, with most of them having an osteopathic or chiropractic training and background. It was this formal training which gave them access to Bowen’s clinic and helped them to compare methods but, paradoxically, may also have restricted their ability to look beyond a rigid format.

Thus when each came to interpret what they saw, each fitted Bowen’s work into a pattern that would match the basis of a structural approach. They looked for indications for specific procedures and created the ‘Structure governs function’ methods as stated by the founder of modern osteopathy, Andrew Still. So, were they wrong in this approach? Not really, as these methods still offer validity as a mechanical and physical therapy and, for the most part, this is how those skills are taught and used around the world. It does however fall very short of the essence of bodywork if this is as far as it goes, especially when Bowen himself said that all he was showing them was 10% of what he knew. It was up to them to go and find the rest. Ossie Rentsch started teaching his interpretation of the work in 1982 after Bowen’s death. He has claimed that Bowen commissioned Rentsch to document the work and on his ‘deathbed’ told Rentsch to go and take it out into the world. This claim, along with many other stories and claims subsequently demonstrated to be untrue, has never been independently verified but it was certainly due to Ossie Rentsch that the work did indeed become as widespread around the world as it is today.

Unfortunately,there is dispute what Bowen said to whom and what exactly he did. Certainly Bowen’s approach was not the result of a Damascene conversion and Bowen picked up and applied many different ways of using his therapy over the years. Some people claim to teach Bowen’s later or “advanced” work while others boast of the purity of the “original” method that they choose to employ.

By reducing Bowen’s approach to a series of moves, the essence of the work is missed, even though these procedures are nearly always very effective. Bowen found a starting point from which he could encourage the body’s own power of healing to take hold. What he actually discovered has huge implications in both the world of modern medicine and the complementary field.